In response to A Fragile Correspondence, journalist Diyora Shadijanova visits the site of Ravenscraig and considers its past, present and potential future.

Wikipedia describes Ravenscraig as a “village” and a “new town”, but when I travel there one sunny afternoon, it’s all roads and roundabouts breaking vast areas of greenery fenced off for future construction. Wedged between Carfin, Motherwell and Shieldmuir, there is nothing there but a pub, a contemporary statue of a steelworker, and a regional sports facility.

I reach Ravenscraig through a series of new builds in Carfin; they are perfectly manicured but seem oddly disconnected from their surroundings. Most suburban developments I’ve seen are like this; they promise community on the roadside advertising boards, but in actuality, price out local people to leave behind an eery uniformity of cheaply constructed buildings with artificial grass in the backyard. There is no history of place, with the only remaining connection to the outside world conducted through SUVs and delivery vans. Is this what the promised Ravenscraig development will be like? That’s what some folks in the area fear.

Ravenscraig, also known as Steelopolis, used to be the site of Ravenscraig Steelworks – the largest hot strip steel mill in Western Europe. Built in the 1950s, it operated and employed around 13,000 workers at its peak until its closure in 1992. The site played a crucial role in Scotland’s industrial history, contributing to the country’s economic growth. Privatisation of industries by the Thatcher government in the late 80s and the early 90s recession led to the plant’s closure, creating a significant blow to the local community as thousands of jobs were cut. This painful history is difficult to gloss over.

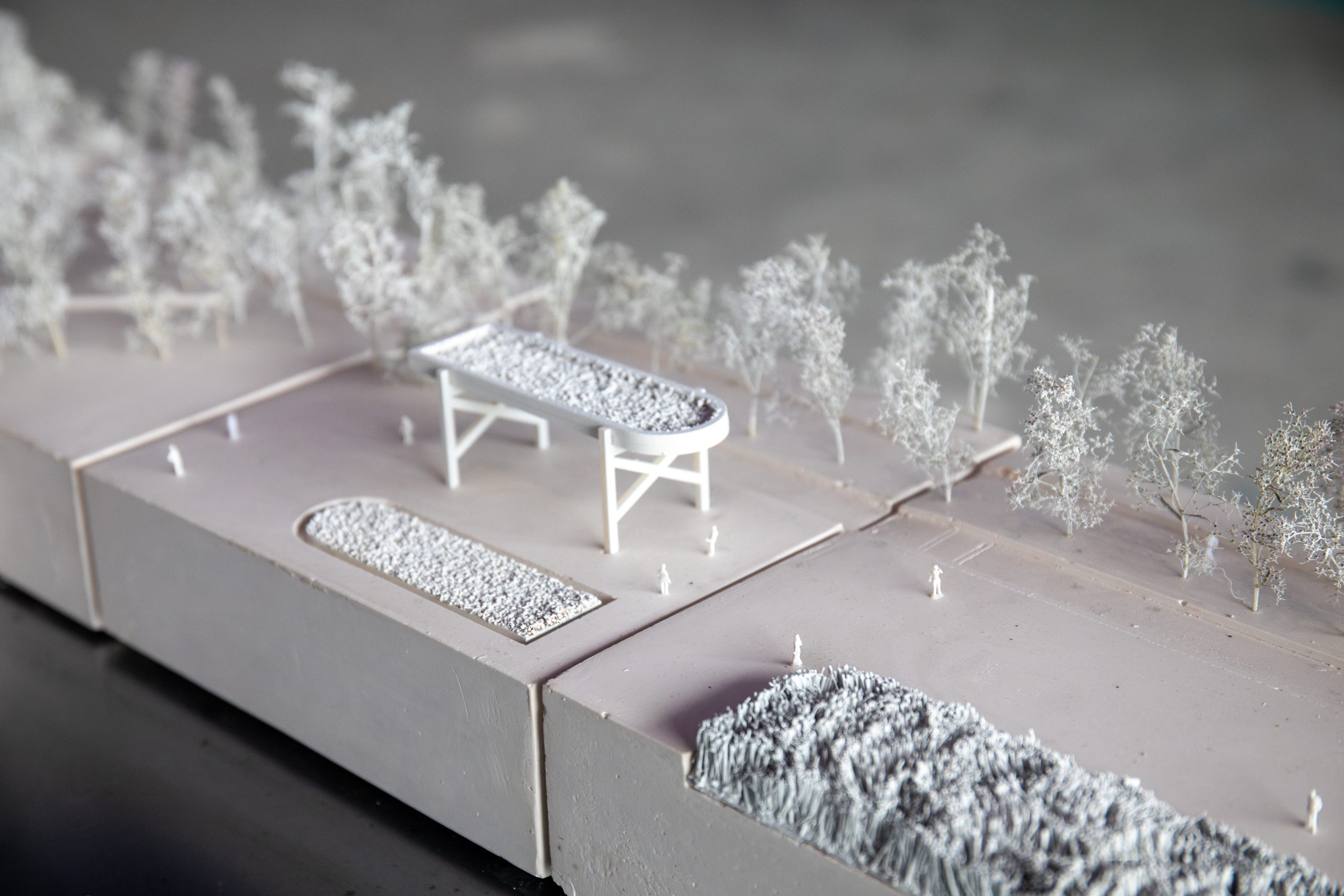

Today, the old site is almost totally demolished and after many years of planning, it is to be “regenerated” and redeveloped by Wilson Bowden Developments Ltd, Scottish Enterprise and Tata Steel. This new town promises 3,500 new homes, a town centre with 84,000m² of retail and leisure space, up to 216,000 m² of business and industrial space, major parkland areas, a new transport network, a sports facility, two new schools, a college and a hotel.

The plans are controversial, with some local residents and businesses of nearby towns worrying the new town will destroy jobs and businesses in the surrounding areas and wondering why places like Motherwell or Carfin couldn’t be redeveloped instead. Still, the council argues it will create much-needed jobs in the area.

There is a plethora of other questions to consider. How will the development of the new town not wash over the site’s complex history of extraction, community, labour, dereliction and toxic waste? Will it be properly decontaminated? How will it foster a sense of community when almost nothing will be publicly owned? To what extent have local residents been consulted in the redevelopment process and the vision of a new Ravenscraig? How many of the new jobs will be green? With construction being one of the major sources of emissions, will the buildings be built sustainably? Will any areas be preserved as a living memory of the site? As trees grow through cracked concrete and wildlife returns to the area, couldn’t Ravenscraig be used as a case study in rewilding a brownfield site? How will wildlife species be adequately protected?

And finally, who will stand to benefit from the redevelopment – the working people or the investors?

Originally published in The Herald, 30 September 2023